Ben Wynne still talks about 3D printing the way people do when they’ve felt that “wow” moment up close.Back in the early 2000s, he was working at HP’s advanced R&D group, and there was a 3D printer in the lab.It didn’t just look like a tool to him; it felt like a shift in what manufacturing could be.

But over the next two decades, as the technology matured, Wynne also saw where the limits remained: “while 3D printing has scaled in some areas, taking it into consistent, high-volume production is still hard, and often expensive.” Today, as CTO of Intrepid Automation, he told 3DPrint.com about how his team is trying to close that gap.Not by pitching a brand-new “do-everything” machine, but by using fast polymer printing to accelerate a manufacturing process the world already trusts: casting metal parts.And for aerospace and defense, where time, supply chain risk, and qualification rules all matter, he thinks that approach could be a big deal.

A familiar story: great tech, hard reality Wynne’s path into additive manufacturing (AM) is a tour through some of the most important corners of the industry.He spent around 15 years at HP, working across 2D printing, scanning systems, and advanced product concepts.He also worked on 3D printing and 3D scanning platforms that never made it to market, something that happens a lot inside big corporations.

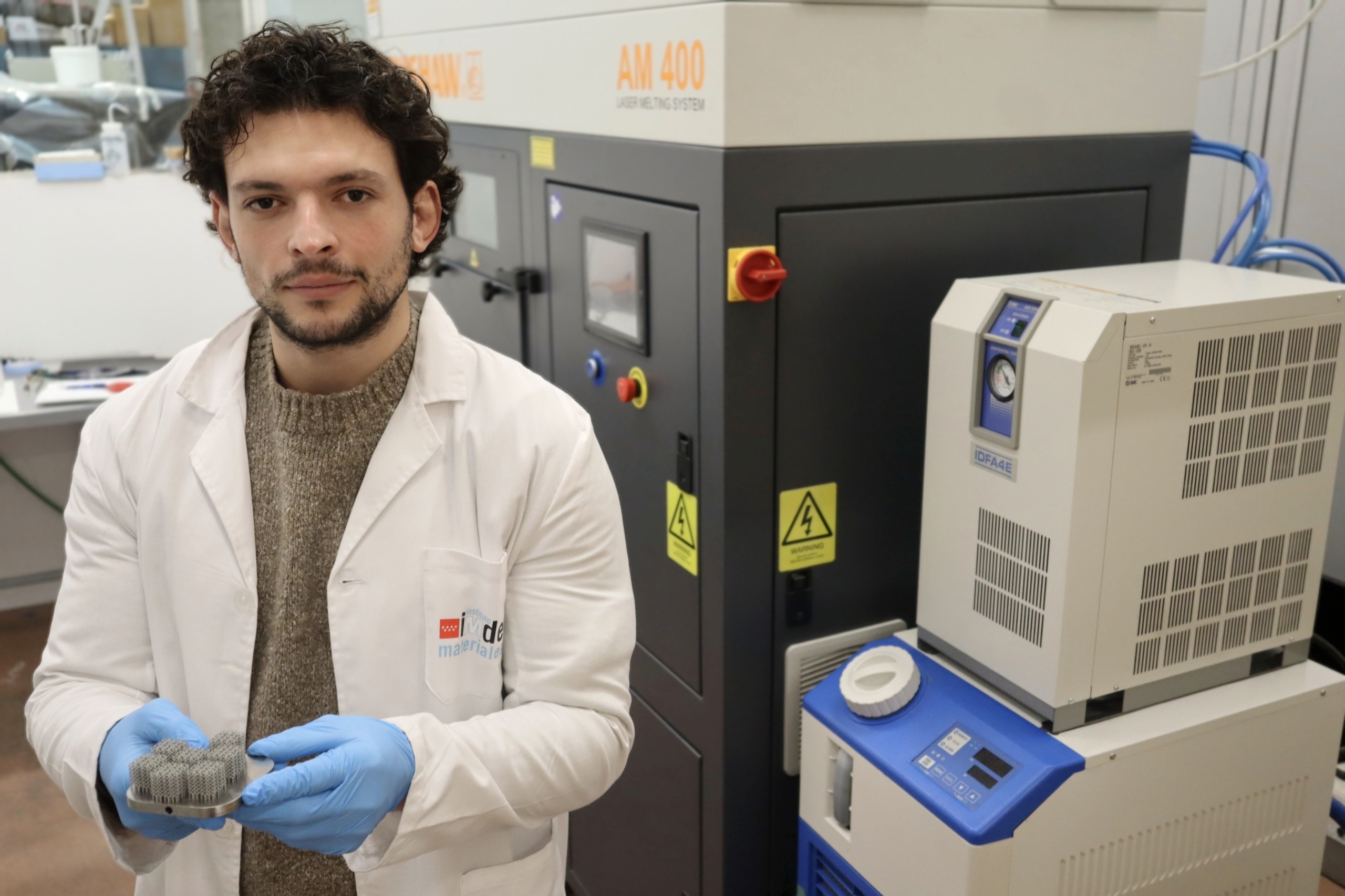

Ben Wynne.“I spent most of my career at HP.My job has always been to look at technology and find ways of applying it to create new products.” Eventually, he left to join a startup called Wiivv (now FitMyFoot), where he tried to build real consumer products using the best additive manufacturing tools available at the time, including selective laser sintering (SLS).

He invested heavily in production-grade equipment and pushed hard to see how far the technology could go.That experience became a turning point.What he ran into “wasn’t a lack of promise, but a set of practical limits, speed, cost, and the amount of manual work required, that made high-volume production difficult.” Wynne told me he wasn’t questioning the value of AM itself.

Instead, the experience helped clarify a specific gap: moving from impressive parts to consistent, repeatable, cost-effective manufacturing at scale.“The bottleneck really has been that additive doesn’t scale,” Wynne said.“Either from a capital investment standpoint, speed, consistency, quality, all of those things have been a barrier.

But to me, that frustration became fuel.” The Intrepid origin: leaving to solve the hard parts Wynne later returned to HP.Then a major shift happened when Vyomesh Joshi, an HP veteran, became CEO of 3D Systems.Wynne was recruited to join.

He helped launch 3D Systems’ San Diego site in 2016 and worked on developing the Figure 4 platform.But after about 14 months, he and others left.In September 2017, five co-founders, many of them with long shared history at HP, started Intrepid because they felt the industry wasn’t fixing the “real problems.” “We didn’t feel like any of those fundamental challenges around part consistency, automation, scalability, and cost were being actively solved.

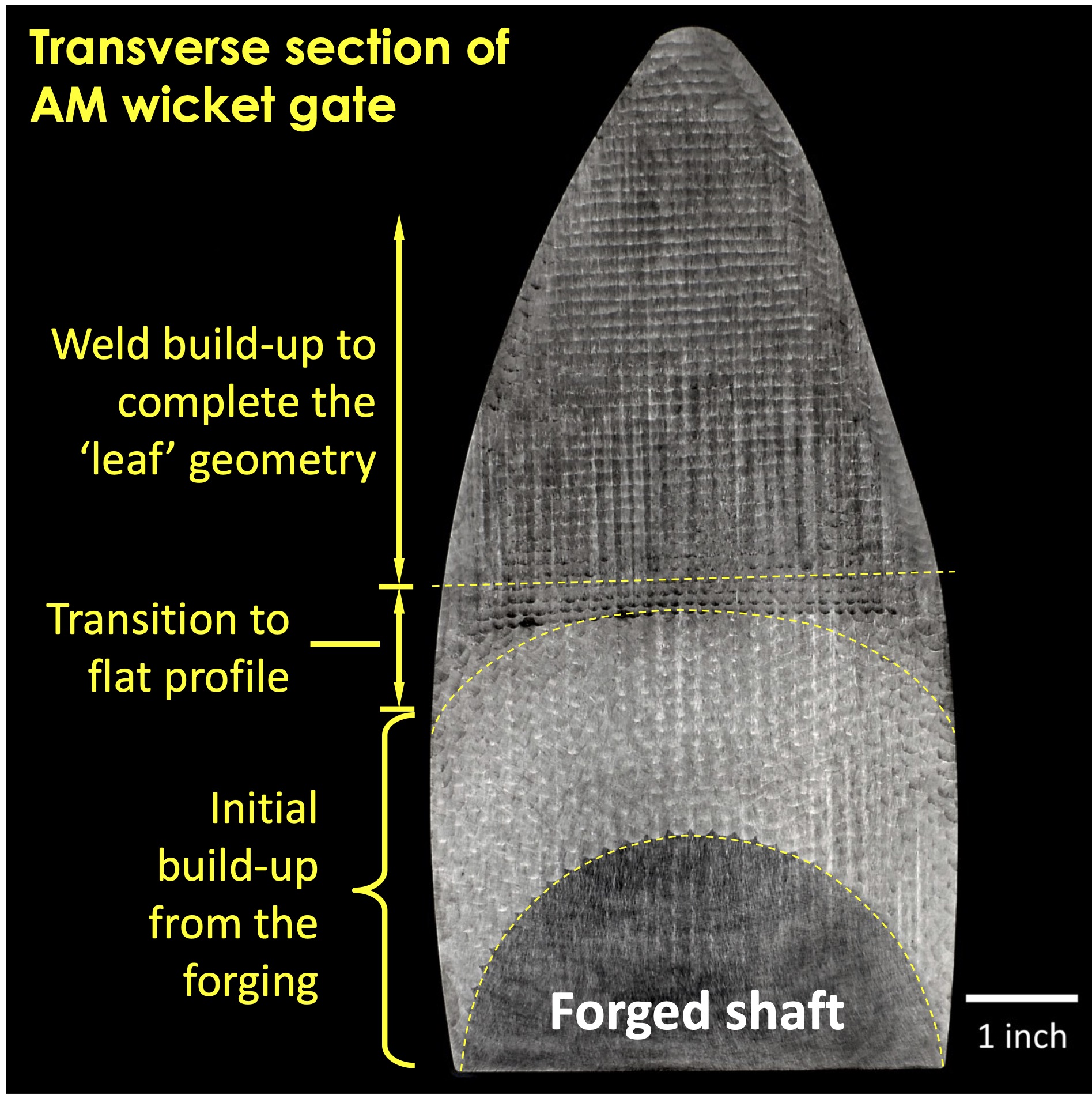

So we went on our own to try to solve that.Eight years later, Intrepid’s goal is still the same: ‘additive at scale for real mass manufacturing.’” But the way they’re doing it is not what most people expect.The company uses fast polymer 3D printing to produce the patterns and tooling needed for casting, so its clients can produce qualified metal parts faster, using existing foundry infrastructure.

People have used printed patterns for investment casting for decades.The concept isn’t new.The problem has been speed, cost, and throughput.

“What Intrepid’s done is we’ve focused on speed,” Wynne said.“We make our own resins, and we can now use digital patterns with existing foundry infrastructure to enable parts to be produced in days and not months.More importantly, that last part matters in aerospace and defense because it avoids a common nightmare: re-qualifying an entirely new manufacturing process.” Wynne explained it with an example: if a military drawing calls for a specific alloy casting, Intrepid’s approach still delivers that same casting, same alloy, same foundry options, same supply chain logic, just with a digital front end, he noted.

“The beauty of digitizing existing manufacturing processes is that, from a regulatory perspective, it is the same.Same alloys, even the same supplier, but just created using a digital technology as the front end.In other words: don’t ask the system to change everything.

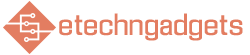

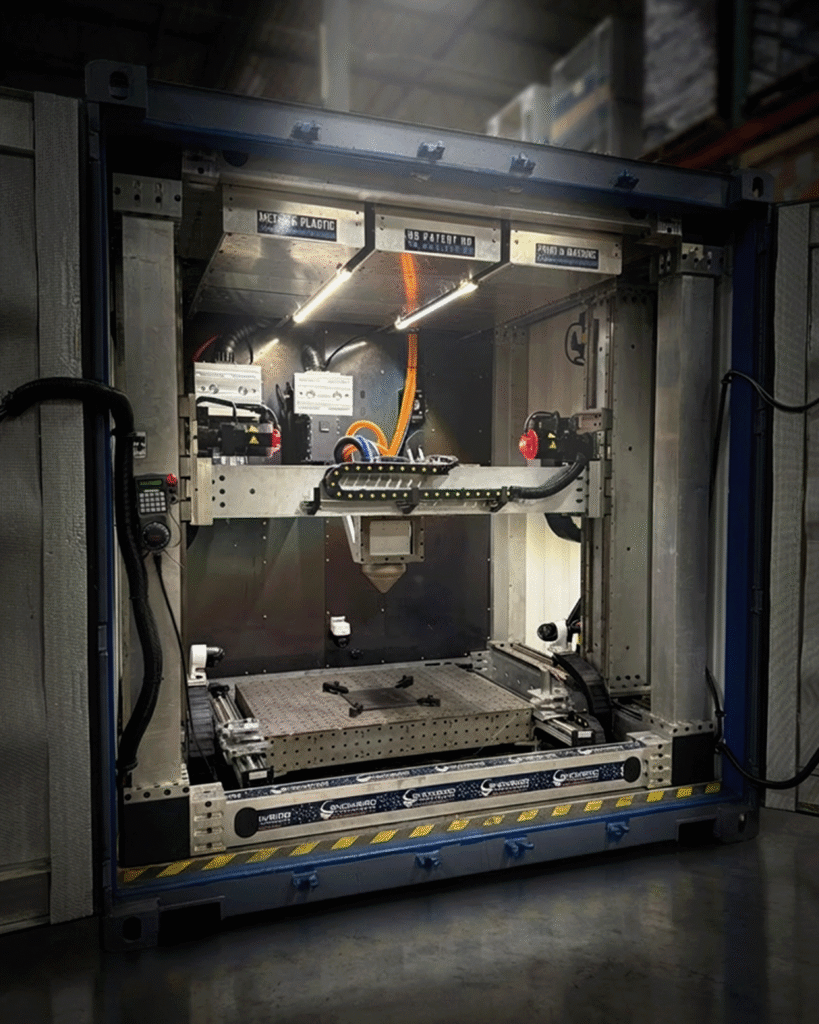

Help it move faster without breaking the rules.” How they print so fast: stitched projectors, not a single beam So, how does Intrepid get the speed Wynne keeps coming back to? His answer is the architecture: instead of moving a laser point across a layer, Intrepid projects whole layers at once.And instead of a single projector, they “stitch” multiple projectors together into one seamless image.“We own patents that broadly cover our technology set,” added the expert.

“We can put an arbitrary number of projectors together and create one massive image.So, instead of moving a laser around like old-school SLA, we have six 4K projectors projecting an entire layer at once.” The kinds of parts his team cares about most are larger industrial geometries.The other piece is materials.

Intrepid makes its own resins, which Wynne says helps them lower costs and open more real manufacturing opportunities.“We want to be able to provide price elasticity,” he said, because there are cases where “the technical may have made sense, but the unit economics didn’t.” Casting isn’t the only target: sand casting and match plates Investment casting is one big target.Sand casting is another.

Wynne described an old problem that still hits the defense world: many legacy parts don’t have clean digital design data.Sometimes there’s no CAD.Sometimes there aren’t even proper drawings, and there’s a real need to digitize that front end, too.

So Intrepid is using 3D printing to create digital equivalents of match plates (the tooling used in sand casting).Wynne said the company can print extensive tooling quickly, and the build area he referenced was roughly 30 inches by 26 inches.He reiterated that they need to add capability to existing manufacturing, instead of trying to replace it overnight.

“We want to be a catalyst for the legacy ways of making things,” he said.“Automation is a big part of that, especially because the labor issue is real.It’s not just a technical problem.

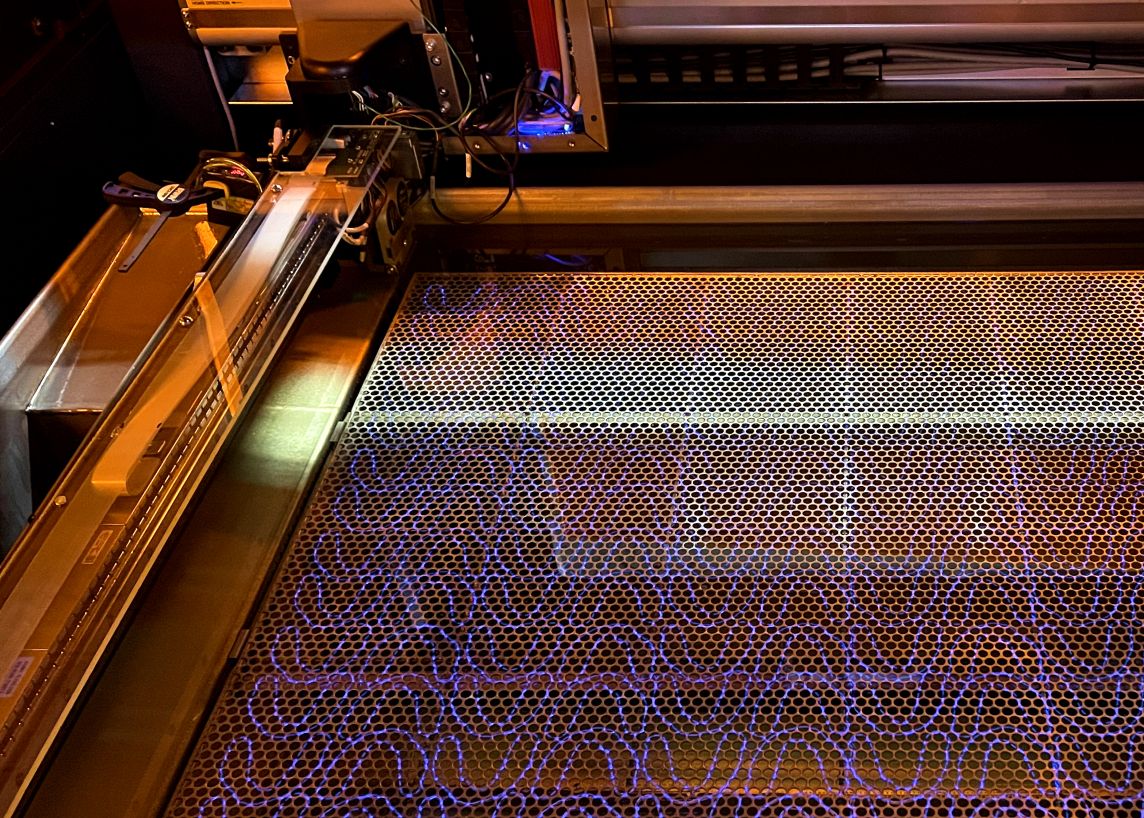

How do we remove the bottlenecks? The answer is automation—systems that can print and post-process continuously, lights-out, with the option to have robots service the machines.That’s how you move forward, not by simply adding more people.” Intrepid’s production systems have names.The automated cell is called Epic.

The larger, aerospace-focused system is called Range (formerly Valkyrie).And Wynne indicated that if the market needs bigger, the platform can scale by adding more projectors.Intrepid Automation’s machines.

Wynne said Intrepid has raised “just close to $30 million” over the years and is “aggressively scaling” its commercial side now that the core technology has been proven.The executive also discussed an ongoing legal dispute with 3D Systems that began in 2021, noting that key claims were dismissed in March 2025 and that the remaining matters are still ongoing.With most of that part of the company’s history behind it, Wynne now looks ahead: “The industry is increasingly focused on real-world deployment.

In aerospace and defense, that requires complete, integrated solutions.Long term, the goal is to build a scalable, modern manufacturing infrastructure.It’s about upgrading what already works.” Images courtesy of Intrepid Automation Subscribe to Our Email Newsletter Stay up-to-date on all the latest news from the 3D printing industry and receive information and offers from third party vendors.

Print Services Upload your 3D Models and get them printed quickly and efficiently.Powered by FacFox Powered by 3D Systems Powered by Craftcloud Powered by Xometry 3DPrinting Business Directory 3DPrinting Business Directory

Read More